Charles Politz

- Melissa Delzio

- Apr 8, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 13, 2020

Northwest Design Work and Mentorship

By Nicole Donisi

Written as a part of the Portland Design History Class at PSU

In Portland, community has always been important to the arts. Few people epitomize this statement like designer Charles Politz. He designed much of the visuals Portlanders saw through the 1960s and 1970s, but his most remarkable legacy may be his mentorship of younger designers. This approach likely helped pave the way for Portland’s collaborative design style.

Charles’ lifelong interest in art led to his elegant style in graphic design. This style also helped to showcase his subject matter, which was often his native Oregon. Never overly flashy, his designs hint at his affection for the soil he lived on most of his life.

Design Beginnings

When I tracked down one of the first books I could find designed by Charles, I was initially a bit disappointed. At first glance, it seemed it was hardly designed at all. However, the book’s subject was the aftermath of the Mount St. Helens eruption. Charles chose to show full spread pictures and accompany it with minimalistic captions in an elegant, non-invasive way. One can really visualize and take in the impact of the blast with this treatment. The design of the book would have likely looked different in the hands of designer who was not from the area.

Highly popular Portland Trailblazer books published by Timber Press in the late 1970s. Charles was hired to design all three and opted to use striking photography on the covers.

His love of his city and state showed in all the projects he applied himself to. Amongst the clients and projects were the Oregon Blue Book, state tax forms, state centennial celebrations, Multnomah Athletic Club, Portland Opera, City Club and books about the Trail Blazers ’77 Championship. Portland area businesses he worked with included Jantzen, Hoffman Construction, Marty Zell & Associates, Salishan Lodge, Museum of Contemporary Crafts, and Legacy Emanuel Hospital. Though many large design firms of the time were thriving on the East Coast, Charles continued to design in Portland and did not venture to a larger metropolis. His friend, native Oregonian Tim Leigh said, “He didn’t feel he needed to and besides he lived here,” gesturing out the window to the waters of John’s Landing in Southwest Portland.

Northwest Roots

Charles was born in Portland on Feb. 5, 1923. He graduated from Lincoln High School. As a young man, he showed an early interest in art by heading a cartooning club with notable Portland designer Byron Ferris. Charles suffered from a stutter and perhaps his aversion to public speaking led him to pursue writing at the School of Journalism at University of Oregon where he graduated in 1945. An article he penned for the Oregonian in 1942 explained how his stuttering affected him as a young man, “I developed a morbid fear of reading aloud which hounds me at time to this day. I entered high school with a 7-cent diploma, an all-E report card, and a well-developed stutter. I had all the standard equipment of a grade-A stutterer—enough fears, anxieties and complexes to fill a bureau drawer. I had telephonics and introductionitis, morbid fears of the telephone and introducing people. These are traits common to all stutterers. My whole life was centered around my speech and what big things I could do if I could only talk.”

While studying at University of Oregon, he contributed written articles to the college publication Old Oregon, chronicling educational and political topics. After trying his hand at script writing in Hollywood in the 1950s, Charles returned to his home state.

An Eye for Design

Once back in Portland, one of Charles’s early jobs was as a print shop worker. At this position, he did not have any input into the design of the jobs he was given. When print jobs came in he was to print them as received, no matter how they looked. As a friend put it, “Obviously that didn’t sit too well with him.” With his eye for elegance, one can only imagine how much Charles must have felt the urge to improve the pieces.

In 1947, Charles began his own design firm, which he named Politz, O’Gogerty & Raskilnov (though the only member was himself). Supposedly, he chose the name because it might convey an ethnic and diverse blend to clients. Later in the 1960s, he became a part of Studio 1030, one of Portland’s most successful design firms. He worked alongside other notable Portland designers including Joe Erceg and Bennet Norrbo and handled projects for Jantzen, Oregon Elementary Schools, Oregon Historical Society and many others. While at Studio 1030, Charles was asked to curate and design the photography exhibit for the Oregon Centennial. He was specifically asked due to his interest in both photography and architecture. He had become especially interested after a trip to Japan where he took many photographs of the architecture there.

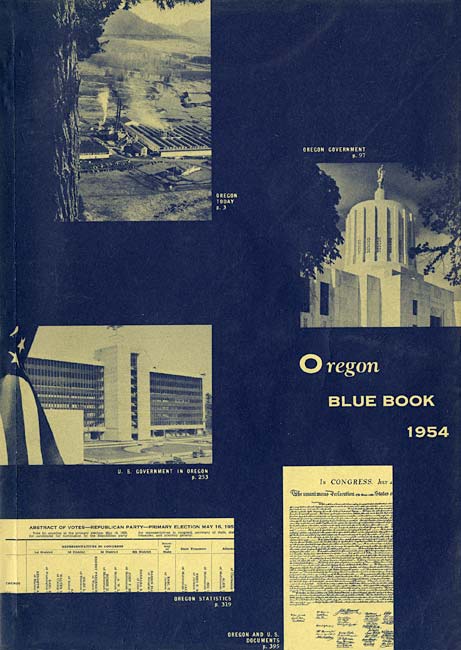

Though never formerly trained, Charles had a knack for design that he honed by continual learning, mentorship and exposure to art and culture. Under “Education” on a 1980 resume, Charles wrote only one word: autodidact (self-taught person). A former colleague recalled he would sit at the drafting table with some type and images and just move them around until it looked “right”. One client was a tool equipment company and his colleague Tim Leigh recalls that once Charles had a hundred or so small photographs of screws, bolts and tools which he kept moving around until the massive arrangement was to his liking. He didn’t always plan designs out with a grid or other tool, he often worked on his intuition. Looking at his cover for the 1954 Oregon Blue Book you can really see this approach and imagine him meticulously arranging the photos.

The Oregon Blue Book is the state’s official almanac and fact book. It contains information on the state, city, county, and federal governments in Oregon, educational institutions, finances, the economy, resources, population figures and demographics. Secretary of State Ben Olcott published the first edition in 1911 in response to an “increased demand for information of a general character concerning Oregon”. The primary goal of the book is to help the citizens of Oregon understand and gain access to their government and related institutions. Early editions of the book were available free from the State. By 1937, copies cost 25 cents; in 1981 the book cost $4. Previous publications to the 1953 edition tended to feature traditional drawings of Oregon scenery on the cover while Charles used a modern design with tinted photography. From left to right: Cover of 1954 Oregon Blue Book. Full photo spread of the capitol in the 1954 Blue Book. Illustrations by Lloyd Allen commissioned by Charles featuring state commissions: Board of Livestock Auction Markets, Board of Massage Examiners, Livestock Advisory Committee and Board of Medical Examiners.Oregonian write-up featuring the new design. A mention in the Oregonian of the exciting new design for the 1954 edition.

Success and Challenges

In 1977 he became a member of Design Council Inc. (DCI), a cutting edge design group who counted Peter Teel, Byron Ferris and Home Groening among its members. DCI handled many accounts both local and national. Charles designed several wonderful logos while at DCI, including work for Hoffman Construction, Boys & Girls And Society, One Pacific Square, Portland Zoo, Contemporary Crafts Association and Gallery, Blaesing Granite Company and Matrix Associates. He likely contributed to many others as the firm was a group of designers who often collaborated without attribution.

Each quarter, DCI released a newsletter highlighting member achievements, sharing design humor and announcing news. One news item included was the announcement of the winner of the “Politzer Prize”, awarding excellent design work in the community. This cheekily named award showed their often absurdist sense of humor.

Left to Right: DCI Quarterly newsletter and its poster back. DCI Quarterly Newsletter featuring logo work by members. Logos by Charles are: Hoffman Construction, Matrix Associations and Portland Zoo. Announcement in a DCI publication of "Politzer Prize" award to Joe Erceg for a downtown mural.

Despite all of Charles’ skills, one challenge Charles faced was pitching designs to clients. He struggled with his stutter when in the spotlight, though friends say it was rarely noticeable in relaxed conversation. However, this never deterred clients. They sought him out for their projects as he was regarded as one of the best designers in Portland, even if it meant waiting patiently while he spoke. His colleague Joan Campf recalls, “If you knew Charles, you knew that he stuttered, and he really suffered from that all his life, but when it got to his artwork he never stuttered a bit. It was fluid, and gorgeous, and honest, and real, and it came out of the inside of him. It either came out of the inside of him as a piece of elegance or it came out of the inside of him as a piece of humor. He really could have ended up as a writer, as a really talented writer, but I think that art bug took him down the road.”

Charles's personal end-of-year greeting cards became collectors’ items and were featured in an AIGA exhibition. They span from years 1938 - 1997 and range from amusing, like the announcement of a new home as a moon landing, to the political: a McCarthy-style investigative hearing featuring Santa and his reindeer. They reflect the zeitgeist of the times in which they were created. They also show his personal love for travel and his artistic influences.

Art as a Lifestyle

Charles became involved in design and from there his interest in the arts never wavered. Through his wife, Eiko, he became interested in Asian art which, later in life, inspired his brush paintings of figures. They traveled together to her native Japan and Charles was very inspired by the art and architecture. She was involved in the art community as well and continues to donate gifts to local Portland galleries. Charles continued his interest in photography and drawing, and in the 1970s he began to exhibit his own drawings. In true minimalist elegance, Charles would attempt to reduce the nude figures down to just the essentials, the smallest number of strokes that still captured the figure’s essence. His embrace of culture and fastidiousness with design helped define him as a figure of good taste. He was highly involved in the arts community in Portland, being a member of arts associations and exhibiting his paintings in galleries. He also designed several books for local artists, including a striking one with metallic pages for sculptor Tom Hardy. Over the years, Charles had made a habit of designing a Christmas card for his friends and family. The cards often featured political cartoons or fine art drawings. Charles could have quite a sense of humor and felt free to express himself with the cards each year. These political cartoons showed the complexities of Charles as a person. He practiced art as a lifestyle and yet his design career was also commercial. Highly respected in his field, Charles chose to encourage new designers rather than regard them as competition.

Mentor Mentality

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Charles often attended Designer’s Round Table, a collaborative forum of young designers, and took an interest in their projects. Many older designers of the day would never have shared their secrets with newcomers. This group was comprised mostly of up-and-coming designers of the day and Charles was often invited to give feedback and advice. He was even asked to design their logo.

Tim Leigh recalls how grateful he was to have known Charles in his early designing days, “He was respected and substantial. He defined good taste. We regarded him with wide and admiring eyes indeed. And do you know what Charles did? From his lofty place, he reached down to us and brought us up. He looked at our portfolios and encouraged us. He took seriously our small efforts and projects. He participated in our groups, offering his skills where they would help. He welcomed us to be with him, and seemed glad when we were. In so many ways, he helped us to recognize ourselves, to find our form and place. It was a precious, invaluable gift.”

It was said of Charles that once he went into design, he went all in. That approach included ensuring a future of emboldened Portland designers and for that we can all be grateful. •

Top left to bottom right: Hoffman Construction logo; Publication design for Emanuel Hospital; Charles Politz and Joan Campf; Logo and envelope design for Matrix Associates; Logo and letterhead for Contemporary Crafts Gallery; Portland Opera promotion 1969-1970; Marty Zells holiday ad; Publication design for Emanuel Hospital.

Documents

Gallery show postcards.

Charles Politz resume sheets.

Comments