Richard H. Wiley

- Melissa Delzio

- Jul 29, 2021

- 31 min read

Updated: May 4, 2025

The Story of Portland’s Most Prolific and Pioneering Illustrator

By Melissa Delzio

Richard Wiley described art and illustration as both his purpose in life and his tormentor; his paycheck and one of the “…greatest ways in the world to make a fool of yourself.”

Over a prosperous six-decades-long career as an independent artist in Portland, Richard’s fashion illustrations helped build up Portland’s reputation as an industry leader in apparel. His humor and camaraderie with fellow independent designers at Studio 1030, in combination with his community-minded perspective, helped build foundational design organizations in this city. Richard garnered national attention as a portrait artist, yet persistent bouts of self-doubt kept his ego in check. But before he laid down the first paint strokes in the Pacific Northwest, he was a young boy with dreams of being a cartoonist in Virginia.

Art as an Escape from Academic Drudgery

Richard Henderson Wiley (known as Dick to his friends) was born July 26, 1919, in Lynchburg, Virginia. His father, Edgar Clarence Wiley, was a prolific mechanical engineer and inventor. By age 18, Edgar already held four patents. Young Richard often felt he was in the shadow of his father’s genius, but he was determined to carve out his own path. Positive reinforcement of Richard’s talents were established early, particularly by his mother who, at age seven, proclaimed him to be a “gifted artist.” This was all the encouragement the young boy needed to launch his artistic dreams.

He started making art for anyone interested (including early portraits of his grandparents) and expressed an interest in cartooning. Notoriety for his work spread by junior high. Richard’s daughter Denise Wiley says, “He was always the guy in school they would go to when they needed a drawing of something.”

“Talented, accommodating, forgetful and obstreperous,” was the 1934 description highlighting a young Richard Wiley in the E.C. Glass High School news weekly, unironically named High Times. The High Times was a publication that balanced out its use of the 5-star vocabulary word “obstreperous” (meaning unruly or boisterous) with the colloquial use of words like, “‘tis” and “‘rithmetic” to convey a down-to-earth sensibility. Regardless, the high school publication wrote a full article about the talented young artist who wasn’t even in high school at the time.

As a junior high school student, Richard was allowed to take Margaret Helbig’s art classes at the high school. Ms. Helbig was an artist in her own right known for landscapes, figure painting and floral studies. About Richard, she expounded, “For he showed such remarkable talent, I suggested that he come to Senior High for extra periods. He takes art ten periods a week and is completely wrapped up in his artwork.” However generous Margaret was, she may also have been the same art teacher whose judgement he battled later in life. The teacher’s proclamation that, “Real artists never use photographs,” stayed with him, and his reliance on photography made him feel like a lesser artist, thus undermining his confidence.

Richard’s early interest in art in school may have served a dual purpose. In a 1971 article, Richard himself admits art was an escape from academic drudgery. He said, “I found out as a boy that I could get out of dirty details like spelling when I could draw pictures.”

In addition to taking advanced art classes, Richard’s prolific talent earned him the position of Art Editor of High Times. A high honor indeed. For the publication he provided cartoons, which were full of insider references to students, teachers and principals. In Richard’s early work, we see almost no examples of personified animal characters; rather we see sophisticated renderings of figures that are anything but childish. Inspiration came right from the comic section of the newspaper, especially the Price Valiant strip by Hal Foster with its more detailed and realistic epic panels. Richard’s characters are drawn in a style that is more reminiscent of 1930s Dick Tracy comic strips than the “rubber hose” cartoon style which was en vogue (for example, the noodle-y limbs of characters such as Felix the Cat). His panels were signed with a signature that resembles the famous signature of Walt Disney. According to his son Ryan Wiley, as a young man Richard, “took a correspondence course in cartooning, where he would get an assignment, draw the character, send it in and receive ‘professional feedback’ and suggestions in return.” This practice and process would be the foundation for his future career in illustration.

Once in high school, Richard was awarded the task of illustrating covers for The Critic, the high school’s literary magazine, as well as programs for musical performances and other design ephemera. A few of Richard’s The Critic covers show bolder experimentation, dramatic lines and the drama of positive/negative spaces.

Richard’s lackadaisical attitude toward his traditional studies and overall class clown status was highlighted in the High Times article, but it seems as though young Richard’s charm and talent won over his teachers to a degree that they made accommodations that steered him on a career path that he stayed on throughout his whole life. In these early days, Richard established behaviors that would serve him throughout a long and illustrious career: an eagerness to please others and a proclivity toward perfectionism that would prompt him to draw the same subject or scene over and over again until he was satisfied. When asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he would proudly declare that he wanted to be a cartoonist.

Lucky for us, he was encouraged by his parents and teachers to follow his ambition and set his sights on attending Syracuse University in New York to study Fine Art.

Richard was as adventurous as he was talented—before starting college, he and a friend took a boat across the Atlantic for a summer of cycling and sketching across Europe. They started together in England, but his friend soon encountered a lady friend. Undeterred, Richard set out on a solo bicycling tour of France. Given his youthful charm and boyish good looks, this cycling American artist was not alone for long. His family recounts that he also made a few lady friends of his own on this journey.

When he finally landed at Syracuse in 1938, Richard set about the task of proving himself in a new territory. Soon he was providing cartoons and illustrations for the college’s student newspaper, The Daily Orange (the official school color). His cartoon subjects ranged from the college-sports themed to the political as propaganda rhetoric heated up in a nation torn about the emerging war in Europe.

In college he began getting paid for his illustration work, freelancing for a very conservative anti-tax newspaper in New York, aptly named New York State Taxpayer. He would submit two or three drawings to the publication’s specifications and he was paid $5 for whatever they chose. He would have a really good month if he earned $20! That would be worthy of writing home to his mother, who would caution him to save some of that money. In some comic panels for the Taxpayer, the sports metaphors and political metaphors combine as in this entry from 1940.

Richard’s work also reflected his hobbies and interests. In Syracuse he picked up skiing for sport and leisure, putting together an informational zine promoting university trips and illustrating a ski-themed cover of The Syracusan, the college’s magazine.

Richard was also a member of an all-male Syracuse cheerleading squad. This may seem surprising given the current demographics of the sport, but the 30s was an era when a majority of colleges were all-male and cheerleading, still a newer sport in the U.S., was dominated by men. In fact, according to an Atlantic article on the subject, “Cheerleading was still seen by some as ‘too masculine’ for women.” One author goes so far as to say that he feared cheerleading would promote the development of women’s “loud, raucous voices.” Syracuse however, bucked the trend on this and had a men’s and women’s squad. Richard, ever the standout, was the only man on the men’s squad to be able to achieve the very difficult forward flip.

Richard’s booming college career would come to a screeching halt, however, after he finished his junior year. He was drafted into the army in the summer of 1941. Richard never returned to complete his degree.

No Shooting, Just Art

The Army Years (1941-1946)

While reluctant to give up college, Richard knew that following his brothers into the army was inevitable in this time of national turmoil. Yet little did he know, his military service would be rather ideal, by comparative standards, and would help him launch his career in design. In fact, it was his talent as an artist and his ambitious nature which prevented him from being sent to the warzone.

Richard was initially stationed at Fort Belvoir in Virginia and later, Texas. One Texas summer day, a day off when all of the other guys went swimming, Richard had a different plan. Ryan recalls the story he heard as a child, “He went to go talk to his commander, to tell him that he was really interested in illustration, and to ask if there was some way he could do that. The commander said yes, as a matter of fact, there was an opening in Portland, Oregon for a map designer.” Richard expressed eagerness at the idea and signed the transfer right there. He then relayed that it was a good thing he had come in when he did, because all the other guys were being shipped out for combat duty the next day. “It changed his life and made all of us possible. If he had gone swimming that day, we wouldn’t have been born,” Ryan says, referring to him and his two sisters.

Richard joined the 29th Topographic Engineer Battalion, one of two active topographic battalions, and the oldest of all U.S. military mapping units.

During war years, the 29th was working on mapping the U.S., particularly the Pacific coastline. They experimented with using aerial photography, replacing guns with cameras on planes for the creation of maps. The Battalion had been stationed in Portland since 1937, transforming the old Glenhaven school in SE Portland (now Glenhaven Park) into a base, complete with army barracks. Conveniently, Richard was stationed right next to the Rose City Golf Course, which in a later interview he laughingly credits to his stellar golf skills.

Richard started making his mark in Portland immediately upon arrival. A 1942 Oregon Journal article showcases Richard’s watercolor “Frustrated Fighter” as part of the 22-man Soldiers Show held at the Portland Art Museum. The exhibit also featured fellow soldier Jack Dumas, who was known for his lively caricatures and who became a fast friend of Richard’s. Richard’s portrait of a soldier was likely not reflective of his own state of mind at the time, as he was enjoying exploring his new city and his illustration career was about to take off.

Many Army mapmakers were also talented illustrators and they were young and hungry for more work. So, after hours Richard and Jack would head to downtown Portland and “scrounge work” from various advertising agencies. There was much demand because so many young illustrators had been drafted. Richard and one Army friend felt they had enough freelance work to warrant renting space in an attic to set up their own commercial art studio. This was Richard’s first peek into what the career of a commercial artist was like.

Racist depictions were common in this era of propaganda.

During his time in the service, Richard also was stationed in San Francisco, working at The Presidio. As he had since junior high, he continued to produce cartoons, contributing drawings to many Army publications. He submitted his inside perspective of Army life to bigger publications, even national magazines like Collier’s and Esquire. The Army took notice of his talent and Richard started making posters with security-related messaging. A major theme of American WWII propaganda posters was to encourage soldiers to keep quiet and to make sure they did not inadvertently give away military secrets while bragging or gossiping.

In a 2009 OPB interview, Richard reflects, “I was in San Francisco and I had a little drawing board and place to work, and a printing press right beside me, and I’d make these posters. I made posters that said things like 'Don't be a Blaboteur,' which is a word that I am proud to say that I invented. I used it until people couldn't stand it anymore.’”

His “Blaboteur” series, encouraging servicemen not to blab, started gaining national attention. A March 12, 1942 edition of The New York Post features one black and white version of the poster and touts Richard’s second place finish in a contest and his reward—a wristwatch. But having his work published in full color in popular national magazine Collier's, was the feather in the cap for the young illustrator. Collier’s had announced a challenge to illustrators across the U.S. that they called the “Shut-Mouth Poster Awards.” Because, “Collier’s believes, as you do, that rumors should be suppressed, that loose talk is dangerous.” The text goes on to use a racial slur against the Japanese that was common at the time.

Racist depictions were common in this era of propaganda.

Collier’s May 30, 1942 issue featured the poster contest winners and among them was Richard Wiley. His Blaboteur poster submission features his witty copy, as well as a blabbing gentleman carelessly giving away military secrets. In addition to having his poster featured in Collier’s in color, Richard received a cool $100 in prize money. In a few short years, he had come a long way from his college freelancing gigs.

Some of the other posters chosen lean heavily into sinister depictions of Japanese people. Richard illustrated a few posters of this nature too, including the New York Post submission. Othering language and racist depictions were typical of WWII wartime propaganda posters internationally, but they are startling to view today, knowing how this propaganda affected Japanese-American citizens during the war period.

Racist depictions were common in this era of propaganda.

During the war, Richard was never sent overseas for combat. He was content to do battle with pen and paper. Denise summarizes her dad’s war years succinctly as, “No shooting, just drawing!”

In 1945, when the fighting was over, Richard and the 29th Topographic Engineer Battalion was sent to the Philippines to begin a “Post- Hostilities Mapping Project.” A booklet about the project authored by soldiers and illustrated by several of the artists, including Richard, goes into snarky detail about the conditions of the ship they sailed on, reporting that “We found there’s nothing quite as refreshing as to walk up to the yawning mouth of a booby hatch and be knocked off your feet by a blast of hot air, redolent with the fragrant, tantalizing odor of beans. Beans for breakfast! Bean soup for lunch, too. Though sometimes, to our disappointment, we were unable to have them for dinner.”

Upon arrival in the Philippines, Richard and the young soldiers saw the after effects of a war zone for the first time. The locals called them “Victory Joes” and tried to sell them loose cigarettes. The booklet states, “In Manila, we saw our first close up of what a 155 does to a brick wall. The Walled City lasted for some three hundred years, but now it looks as if it had been gone over with a big potato masher.”

Scans from 1945 "So We Went Overseas". Richard marked his illustrations and paintings with a red check.

The soldiers moved about via their own fleet, revelling at the site of sunken Japanese ships in the water below. They travelled with cameras and sketchbooks, taking in the scenes. Richard’s captions with his drawings (copies of which he sent home) describe locals gathering around him to watch him draw. He enjoyed the attention. One caption cites, “Ants nearly ate me alive before I finished this one.” The booklet of their experience, complete with many of these photos and drawings, was bound as a memento for the men who served and is called, “So We Went Overseas.”

Richard, now 27 with his Army years behind him, was free to move forward with his career ambition, to become a commercial illustrator.

The Wolf of SW Washington St.

In January of 1946, Richard set his sight on the epicenter of the design world: New York City. He made appointments, met with people and found out very quickly that the reality of working as a commercial artist in the big city meant that it would be many years before he could make a living. It was—and still is—very competitive and expensive to live in New York City.

Meanwhile, his Army buddy Jack Dumas, whom he had worked with in Portland, started wooing him. “Come back to Portland!” he said. “You can start working with us here right away.” Richard had loved Portland, with the mountains and the beaches close by, so it wasn’t a hard decision to make.

As Jack promised, Richard’s career took off when he arrived back in Portland and started work at the Associated Designers studio. Associated Designers was opened in 1946 by illustrator Pers Crowell, and was first described plainly as, “Six Portland artists work independently for Pacific Northwest Industries”. Associated Designers is the studio that later became Studio 1030, when they grew in size and moved to 1030 W. Burnside. In these early years, the studio was located in the New Fliedner Building at SW 10th and Washington. The concept was the same; a collective of creatives with different skill sets who rented a desk from the studio head. The designers collaborated and shared work often. A secretary would manage incoming requests, run errands and often model for illustration work.

On the day Richard was set to arrive for his first day of work, Lois Wilma Wilson was the secretary at Associated Designers. A Portland-born Grant High School graduate who had her own artistic ambitions, Lois heard from Jack Dumas about the new illustrator arriving. Her daughter, Denise explains, “She heard they were getting this new guy. They called him ‘The Wolf’. He was preceded by a reputation as a real ladies man. She thought he would have a long chain watch swinging around and a zoot suit. She met him at the elevator as everybody came to meet him and she thought, ‘Wolf?!? This is no wolf!’” Richard had arrived with saddle shoes and clothes that didn’t quite fit right because he was fresh out of the army. The other woman in the studio had said to Lois, “Stay away, he’s mine!” And Lois told her, “No problem!” Lois had her own plan in the works. She was set to depart from Portland with a friend to try to make it in Los Angeles. Their plan was to lounge at the beach by day and work theater jobs by night. Unfortunately, their plans fell through when they found L.A. to be too competitive. When their money ran out, they boarded a train back to Portland.

Luckily, Lois found Richard right where she had left him. Apparently, the other woman in the office had no luck with “The Wolf” and Richard, smitten with Lois from the start, was brave enough to ask her on a coffee date. Thus their two-year courtship began, resulting in their marriage in 1948. The newlyweds rented an apartment downtown on SW Jefferson. Their first apartment, like all their subsequent homes, was thoughtfully designed and curated, as they both had a knack for interior design.

In addition to finding love, Richard was figuring out how to build his career. Even in the 1940s, apparel was king in Portland, and in order to make a living, Richard learned he would need to embrace fashion illustration—or as he later called it, “figure illustration”. This was illustration’s heyday, before photography became the default in fashion advertising. His first freelance job as a member of Associated Designers was for Lipman Wolfe, Portland’s grandest department store. Richard later recalled, “One day, the Lipman Wolfe department store in Portland had a job they wanted for men's hats. I'd never done an assignment like that before.”

The members of Associated Designers had a lot of fun at work, as evidenced by several entries in a gossip/culture column that ran regularly in The Oregonian titled, “Behind the Mike.” A 1949 entry describes a particularly potent office prank: Richard had been drawing a picture of smelt, using a real, dead fish as a model, and according to the report, when he finished, “ …He thought it would be a shame to throw such a useful fish away.” So, he scotch-taped it to the underside of colleague Pers Crowell’s chair. Pers apparently didn’t hunt for the source of the odor; rather he opened a window, resisted being at his desk and complained of feeling ill.

Eventually Pers was made aware of the prank and weeks later, the Oregonian followed up with a report that he got Richard back by placing an ad saying that Richard (Dick) was an expectant father in dire need of a baby carriage. The Oregonian reports, “Fighting a deadline on a rush art job, Dick has had to spend the better part of two days on the phone explaining to irate women that he’s really the victim of a revenge plot dating back to a dead fish. At any rate, Dick has made up his mind on one thing. ‘If I ever do need a baby carriage,’ he says, ‘I’ll be sure to advertise. It certainly gets results.’”

Indeed, Richard and Lois were soon in need of a baby carriage with the birth of Denise in 1951, then later Ryan in 1954 and Lyn in 1957. Right before Lyn was born, the couple decided to build their dream home on a beautiful lakefront property in Lake Oswego. At a $34,000 price tag, they built a mid-century modern house on the lake that Richard and Lois both helped design. Ryan says, “Dad said he made two great decisions in his life: marrying our mother and building that house.”

Richard would commute daily by bus to Associated Designers in downtown Portland. Richard’s children remember their father’s days working downtown, saying they used to rush to meet him at the bus in hopes he would buy them candy, which he often did. Sometimes, Richard’s own artwork would adorn the bus. Daughter Lyn Blessing remembers she would be, “…riding the bus downtown and his ads would be on the rack on the top of the bus. I was so proud that my dad’s ad was there, I could recognize his art on those old blue busses.”

People Sell People

Richard’s work found an even bigger canvas in a series of billboards for Washington-based Olympia Beer. Richard’s 1956 billboard series exemplifies the evolved sophistication of Richard’s illustration style. The Olympia Tumwater Foundation has an archive of this work and they report, “The original paintings offer a unique glimpse into the art and advertising processes of the day. Completed long before computer technology …most of the pieces were produced by artists (like Richard) hired by the Seattle advertising agency of Botsford, Constantine & Gardner.” The archive goes on to give insight into the process of billboard-making, “In the 1930s and early 1940s, a billboard painter used each small painting as a guide and hand-painted the large-scale version onto a billboard. Later, when printing processes improved, the original paintings were enlarged and printed onto heavy paper—installing billboards then became a much simpler matter of pasting sections of paper, much like wallpaper, onto the wooden billboard backing. Up to 24 or 30 sheets of paper constituted a billboard.”

While the Olympia billboard project was a career high point, fashion illustration was Richard’s bread and butter. Richard had slowly gained the trust of big name apparel clients based in Portland like White Stag, Pendleton, and Jantzen. A 1954 article in the Oregonian’s Northwest Magazine named Portland as a top apparel center; the “world’s largest producers of ski-wear and swim sits, umbrellas, sportswear, leather garments, sweaters…and straight work clothing.” The article highlights the elegant side of the industry, with beautiful models in high demand, as well as “fashion artists” like Dick Wiley, shown with his sketchpad drawing a female model in White Stag clothing.

The reality was not quite as glamorous as the magazine describes. For one, Richard rarely drew from real life, instead preferring to use his camera to shoot his models in the clothes in a variety of poses. His son Ryan describes, “He would use anyone he could to model, very rarely professional models. Lots of family, friends, neighbors, our school chums.” Denise remembers one particular living room scene, “I was just thinking of Jack and Tom (the neighbors) in the living room trying on White Stag clothes, with me running back and forth peeking,” she laughs as she recalls her spying attempts. To get the proper look, Richard was resourceful, even going to furniture and department stores asking to borrow furniture as props for his work.

His children became models when he was tasked with illustrating the Jantzen swimsuit line for kids. Ryan jokes, “Yes, I am a swimsuit model.” Richard would get Ryan a little stool so he could pose on it like it was the pool ladder. “He would ask me to pretend like I was coming out of the pool. He would take picture after picture, saying, ‘OK curl your hand this way. OK, hold it right there.’” Richard would art direct his models until he got the scene just right.Once he had the shot, he would take the film and he would develop it in the bathroom. Ryan explains the process from there, “He would have strips of film hanging everywhere until they dried. He would cut them up and have them printed … in downtown Portland. He would come back with the printed pictures. He marked the ones he liked, put crop marks on it and would start with sketches. I don’t know if he submitted the rough sketches, but at some point he would share initial work with the client. And they would say, ‘Oh good, but double check this pocket, this pocket looks way too big on the item.’ So he would go back and do that, and eventually churn that out. And that would be the ad.” Richard primarily used gouache for the final commercial artwork, never airbrush. He did not set type or do custom lettering, but sometimes would draw the letters from a logo.

There were some things Richard was called to illustrate that he could not take custom photographs for. For that, he kept a huge file cabinet of reference photographs. Ryan reminisces, “He was forever tearing things out of magazines, leaving piles of them and then hiring us for 25 cents an hour to file them for him.” He would have hundreds of photos on each topic—look up “h” in the filing cabinet and there would be piles of horse photos. Ryan describes his father scouring every magazine he could get a hold of. These reference libraries were a necessity for illustrators in the days before a Google image search could return thousands of results on command.

Being connected to the other designers at Associated Designers made it easy for Richard to stay connected to the small but collaborative creative community. He was a charter member of the Portland Art Director’s Club, which started sometime in the 1950s. According to fellow member, Tom Lincoln, the club was formed to “talk shop.” He says they exchanged advice about client relations, establishing business norms around billing and worked to try to elevate the perception of commercial art in the community. Like design organizations today, the Portland Art Director’s Club had an awards show and in 1957 Richard won an award for a Seattle Transit ad he designed for Cole & Weber, a popular ad agency.

By 1960, Associated Designers had become Studio 1030 and moved to their W. Burnside home (in what was most recently the Fez Ballroom). The studio had sales sheets made up to promote each independent artist. Richard’s states, “With his wife and three children, he likes to get away from the world of art and into the world of physical activity…golf, swimming and boating. Other than being an ex-Virginian, he will confess to no other interesting personality traits. We are proud to have him on this area’s advertising team.” Even in his sales sheet, Richard was humble and self-deprecating in his sense of humor.

Another Studio 1030 sales sheet from the early 1960s states: “Action drawings of people—in color and in black and white— are the specialty of Dick Wiley of Studio 1030. …People sell people. When real people—consumers, that is—see Dick’s people enjoying the taste of a certain beer or looking well-dressed in a certain brand of clothes, the real people are motivated to do likewise.”

Richard Wiley’s illustrated ads set mid-century trends for a privileged, white audience and he was about to get a national gig that would—for better or worse—define his career.

Meet Sally, Dick & Jane

In 1958 Richard received a letter from a New York artists’ representative inquiring about a project for a publisher who promised consistent work. The recruiter was reaching out to Richard on behalf of Scott, Foresman & Co, a book publisher out of Chicago that specialized in books for early readers.

The publisher had seen an illustration that Richard had made of a young middle class white family at play in their suburban home for the West Coast Lumberman’s Association. This illustration style was just what they were looking for as they sought to add a new illustrator to their roster for the very popular Dick and Jane reading series, which they were planning to update.

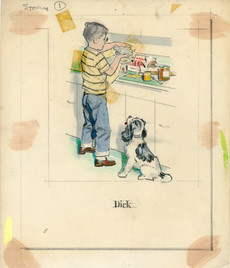

The Dick & Jane series was thirty years old by the time Richard lay the first paint stroke bringing to life the characters: older boy Dick, his sisters Jane and Sally, Puff the cat and Spot the dog. Very popular with the baby boomer generation, the books were “…first published in 1930 and used simple, repeated words alongside illustrations to teach young students to read,” according to an official source.

Richard, along with others, illustrated this book series until its demise in 1965. His association with the famous characters earned lots of press and attention and most importantly gave him a much needed stable income. When asked what Richard was trying to accomplish, when he drew, Sally, Dick and Jane. Richard honestly replied, “Make a little money!”. He went on to say, “They made you make money because of the deadlines. If you didn't get it done on time, you could forget it. The prices for the illustrations were established and they made you do it promptly, and that was good financially… for me.”

Final illustrations, process photos, and sketches for the Sally, Dick and Jane reader, "Guess Who."

The process of working with the publisher was much like his other clients. He would start by reading the story and work up some quick sketches to sell them on the concept. Richard recalled in an interview, “If that was the way they’d visualized it, they would send it back with an ‘OK.’ Otherwise they would write back with their idea of what changes needed to be made. I would sketch, a little more refined than the original, and send it back to them and we’d go back and forth maybe two or three times.”

In a 1980s article, Richard remembers one instance where the publisher rejected an illustration that showed “…two kids chasing each other, then one grabbing the other’s hat. They said that will cause kids to behave in a raucous, hooliganish manner.” This back and forth creative process meant a lot of time and money mailing art across the country.

Feedback and process work for "The Singing Cave", another book by the same publisher.

Then came the time to produce the final art. “I would need (children) as models to make more realistic paintings,” Richard notes. Luckily, a good friend of Richard’s was the principal at Lakewood Elementary School in Lake Oswego. He would let Richard browse school photos to find children that would be a good model for the scene he had in mind, ask the family’s permission, and take photos of the children for artistic reference. The families would generally be thrilled to participate. Like his other commercial work, Richard would use his own children and their friends as models too, sometimes filming them playing and then choosing stills for the action shot he wanted.

Richard had to get creative when he couldn’t find an exact reference image. He remembered, “One time I even put a little extra hair on Peppy, our terrier, and made a cocker spaniel out of him for one of the book pages.” He said he always struggled with the little fuzzy animals. When all was complete and the client was satisfied, Richard would send off the final paintings in time to meet their tight deadlines.

By mid-century, the publisher was catching a lot of heat by readers, educators and politicians who noted a lack of diversity in the books. A subcommittee of the House Education and Labor Committee even held a series of hearings on the portrayal of minorities in schoolbooks. The Dick and Jane books became a powerful example of racial exclusion.

One reader, Jennifer Karen Lawson, spoke during the hearings before Congress, “I realized I was born Black when I went to elementary school and they told me about Dick and Jane and Bow and Wow and… I knew it wasn’t me.”

In response, the publisher introduced a Black family: Mike, Pam and Penny in a 1965 book titled, Fun with Our Friends. Listed as an illustrator was Richard Wiley. Richard was proud to integrate the series, but many white fans were not pleased with the changes. To pacify the white audience, the publisher asked all the book’s illustrators to be sure not to include any “black features”. The character’s skin could be black, but they essentially white-washed the characters to make white people more comfortable. Perhaps these decisions and a shifting political environment led to the demise of the series in 1965. In a year of protest and shifting cultural values, these abundantly white and class-privileged characters were no longer resonating with a restless nation. Richard later reflected that the demise of the series didn’t disappoint him too much. “I wasn’t real sentimental about Sally, Dick and Jane. In particular that cat …Puff, I didn't like that cat.”

By the mid-60s, Richard decided to move his freelance practice home and he turned the majority of the family’s garage into his new studio. Since the Army, Richard had never been an employee, instead choosing to work independently within the design collective for about 20 years. He had built up such a reputation that he could successfully work completely on his own. And, being home meant no commute! Richard could lean into his “workaholic” tendencies while still seeing more of his family. While I’m sure he missed the camaraderie of his colleagues at Studio 1030, he kept many (like Bennet Norrbo) as close friends. He still found ways to give back to the creative community, including as a guest lecturer in the 70s at Museum Art School, now PNCA.

Lake Front Road

Denise describes her father’s work day during the era when he first moved his office to their garage. “He would go into his studio in the morning. He would come out for coffee time and to watch The Dick Van Dyke Show. And then go back in. We felt really lucky if, in the summer, he would come to the dock to take us skiing.”

Freelancing from home had its perks, but perhaps it also added stress. Ryan says, “A freelancer is always under a lot of pressure. There were times when he was really busy and the money was flowing in and there were times when Mom would say, ‘You’ve got to do something.’” Lois was in charge of all paperwork, bills and money; managing the business side of things. Richard worked from a flat fee, one that often caused his family and other designers to gawk. Ryan says, “He was very underpaid, everybody in the business told him that. He was reluctant, but he would finally agree, ‘Well maybe it should be $100 more…’ His colleagues would say, ‘No, it should be $1,000 more than that!’”

Richard continued to do commercial illustration work until the illustration style he had cultivated began its slow decline in popularity. In addition to the increased demand of photography in ads, Richard also cites the boom of commercial television as a factor for the disinvestment in custom illustration. Media buys for TV commercials took up an ever-growing portion of a client’s advertising budget.

Richard later reflected on this shift, “In 1946…When I began doing commercial illustration, about 80 percent of magazine and newspaper illustrations were paintings and drawings. Now I’d say 90 percent of the work is photographs. …When I broke into commercial art, the illustrator was king. I sold work you couldn’t give away now.” But Richard, now in his 60s, was not ready to retire. Rather, he primed himself for a reinvention and a return to his roots.

Patent #4428648

Patent #4428648 was filed on November 25, 1981 and the entire Wiley family was celebrating. Though his inventor father had passed long ago, Richard Wiley had officially followed in his footsteps with the filing of his first patent. The family marked the occasion with a party, complete with a cake decorated with the patent number. Richard’s invention, the Magni-View, first launched in 1982, as a “Transparency Viewing System” that sold for $98.95. It consisted of an adjustable tripod, with a wooden viewer that allowed you to place your slide in a slot and view the slide through a magnifying lens with natural light. No projectors or electricity needed!

The patent application lays out the problem Richard was trying to solve, “The known prior art devices are clearly not suited for use by one engaged in the artistic reproduction of a transparency as they (are) intended for holding within one or both hands. No provision is made for the optimum stationary positioning of the viewer with respect to a seated or standing user, nor is provision made for utilizing whatever source of illumination is at hand. The use of slide projectors is unsatisfactory by reason of heat damage and fading of the slide as well as the consumption of costly projector lamps. Further, the projection of slides causes them to be "washed out" by room light. Color prints as a reference are costly and of varying color reliability.” Richard’s solution offered the best quality color viewing and it could be used anywhere natural light was found. He is quoted as saying, “If you have light enough to paint by, there is enough light to use the little devil.” Richard had designed the device and had it manufactured by a cabinetmaker friend.

To promote the product, he placed ads in American Artist magazine, which garnered him orders from as far away as Argentina. He designed and produced his own packaging and distribution, even engaging family to help. Denise recalls, “It was a family business. At some point, it was in my basement; I would set out four or so for the UPS to pick up every week.”

Of course Richard leaned into his Portland network for support and as a customer base. In a letter to a friend, Richard wrote, “They are being produced at last, and they are beautiful! Each one is carefully handmade of Oregon hardwood with nice traditional styling that makes it a handsome piece of studio equipment. I am really excited about them and I think you will be too. The first time you see one of your favorite color slides, big, bright and undiluted by studio lights! The effect is very life-like.” Richard sold 300 viewers in his first year in business, and business remained slow and steady for a few years after.

Finding the Soft Edges

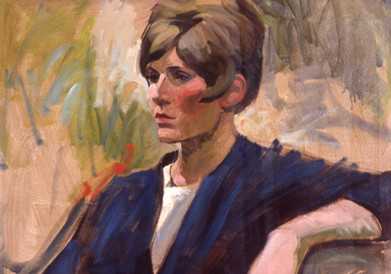

With his career in commercial illustration slowing down, Richard returned to his first love, portrait painting. Luckily this was a skill that he was in his prime for, even if he had to be convinced of it. When it came to fine art, Richard suffered from a crippling case of what we might now call “imposter syndrome”. Ryan says, “He was a lifelong worrier and it was torture for him. He just never had the appreciation for the level of talent that everyone else thought he had.”

In commercial art, the deadlines and strict project parameters kept Richard on track, so there was little time to think and rethink. But on a commissioned portrait, Richard would spend months painting, never quite sure when it was done. At times he would face the canvas to the wall to take some time away from it, only to come back and start over. Richard’s grown children lament the fact that their father seemed to really suffer under this lack of confidence. “He would think, ‘It’s not done, I’m a complete failure, why am I doing this?!’ Meanwhile, everybody else in his orbit was telling him, ‘This is gorgeous, how do you do this?’ But he didn’t buy it,” Ryan recollects.

Friends and family portraits

Even though Richard had built a successful career in commercial illustration and was clearly a talented artist, his high school teacher’s judgement still circled around his brain. At some level he still believed he wasn’t a “real” artist. In an interview in 2009, Richard reflected, “I always take photos before I start on a project. My high school art teacher used to say that you wouldn't go to heaven if you painted from photographs, you'd go to the bad place. I don't think you will, but if you will, then I guess I'm headed for the bad place, because I came out to be a pretty good photographer when I was still working.”

With no strict deadlines, the hardest part for Richard was figuring out when the painting was done. Sometimes, Lois decided for him when their monthly finances came up short, she would nudge the anxiety-ridden artist along.

In 1980, at Lois’s encouragement, Richard took an artistic career risk. He battled his own self-doubt and boarded a plane to New York City to attend the prestigious National Portrait Seminar (a popular conference). This was a full 34 years after his early experience in NYC trying to make it as a young illustrator. He brought with him a canvas of a young Portland girl holding roses, painted in broad strokes to be entered into The National Portrait Competition. He also brought along his Magni-View (in prototype) and had awed enough fellow artists that they demanded an on-stage presentation of the device.

Richard’s risk paid off, and the nervous artist came home with an award for “Best of Show” and $1,000 in prize money! The news of the national prize earned him glowing reviews in local papers and a victory lap display of the winning portrait at the annual Lake Oswego Festival of the Arts in 1981. A 1980 article in the Statesman Journal called Richard “balding and puckish” but did declare that the 61-year-old Lake Oswego man had finally arrived as a fine artist.

Richard painted hundreds of portraits; not just because he received hundreds of commissions, but because for every commission he painted two complete paintings, giving his client options, just as he had done in commercial art! This was in addition to sketches. Richard considered the sketches and the extra portrait option as “insurance,” so that the client would not be surprised with the final product. He overworked to make up for his own insecurities. Richard believed that portraits—even ones painted from a photo—told much more of a story than a photo shot on film. More personality was revealed in a portrait and the artist works, “more by instinct than design”.

Despite being tortured by the creative process, Richard was proud that these works became treasured family artifacts. “People appreciate a good picture of themselves. And I’ve had a lot of people say, ‘If my house caught on fire, that’d be the first thing I’d rush in and rescue: the portrait you did of my little girl.’”

In addition to family portraits, he was commissioned by organizations, such as the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1982, when he was asked to paint a portrait of actor Dennis Weaver as Chester from Gunsmoke and in the year previous, of Paul Tierney, a World Champion Cowboy. As if to balance out the story of the American West, in addition to cowboys, Richard also painted striking portraits of several Warm Springs tribal leaders that hung at Kah-Nee-Ta in Oregon.

In a 1998 article, Richard describes his style as traditional, while reflecting on shifting artistic trends, “Others are more modernistic and I admire them all. I’m still trying to do what was done to perfection 100 years ago.” While the demand for his portrait work was in the traditional style, Denise recalls, “He always wanted to paint with a more bold brush style.”

Richard did show some evidence of experimenting with deviating from the expected style. In 1999, Richard showed a variety of painting styles at PNCA’s Philip Feldman Gallery, at their former NW Johnson location. The show promised that it, “…Could offer nearby art students a lesson in how to convey a range of ambiguous meanings with a limited number of physical gestures and color schemes.” Richard participated in the creative community, even in his later years. He attended the Sitka Design conference in 2004 with other notable figures like Byron Ferris, Joe Erceg and Mark Norrander. At this conference, they discussed the very idea of a need for a Portland Design History project. Over 16 years later, I am proud to have taken up the baton.

Laying Down the Brush

Richard knew he would eventually retire, but he wasn’t quite sure when. Unfortunately, a sudden deterioration of eyesight decided for him. He struggled with issues around glaucoma, which a surgery intended to fix, but the procedure was botched. Ryan laments, “You can’t be an artist with one eye.” Denise adds that the loss was devastating for their father. “The loss of eyesight took away his choice.” He tried to paint some of his grandkid’s portraits at home, but his eyesight became too poor. In their later years, Richard and Lois eventually moved from their lakefront home to Tigard. Richard enjoyed spending quality time with his grandkids, and would noodle around on the keyboard to stimulate his creative side, but soon a series of strokes caused his health to deteriorate further.

As an artist, Richard had struggled with the finality of knowing when a painting was done. A Statesman Journal article from 1980 poetically stated, “He knows he’s got to lay his brush down. If he doesn’t, the painting will go on forever.” In life, Richard also struggled with laying the brush down. Denise acknowledges, “He didn’t live happily ever after.” Ryan adds, “The strokes stole a lot of his personality and his ability to communicate well. He became not Dad anymore.”

Richard’s colleague from Studio 1030, Bennet Norrbo, felt this loss too. He visited his old friend at a care facility in his later years. And Denise recalls that Bennet’s deep sadness at his friend’s fate was palpable. Richard Wiley died in November of 2013, at the age of ninety-four.

In his life, whether he was illustrating a family on vacation promoting Oregon travel, or putting the finishing touches on the painting of a small girl with roses, Richard expressed a tenderness and warmth in his work. His talent was in showing the humanity of all of his subjects; from little fictional Sally to a venerated Warm Springs tribal chief. A good portrait artist needs to be able to truly see people, to read them and empathize so as to imbue the painting with personal characteristics. As Richard put it, “…to find the soft edges.” Richard had all of these skills—and more. He had a kind manner, good humor and an inherent charm that put people at ease, wedded with a lifelong passion for art and design.

Big thank you to Ryan Wiley, Denise Wiley, Lyn Blessing for allowing me to interview them about their dad, and for all of their work prepping and scanning their father's work!

Thanks to Mandi Middlestetter for her keen copywriting eye!

If you have a recommendation on who we should feature on Portland Design History, please reach out to: melissa@meldel.com.

ADDITIONAL READING

The man who 'killed' Dick and Jane

By Geoff Pursinger

Wednesday, December 02, 2009

See Dick. See Dick illustrate. See Dick illustrate children's books. For more than 40 years, Richard Wiley, of Tigard, had a long and distinguished career as one of Portland's premier commercial illustrators, designing advertisements for Portland clothing giants such as White Stag, Jantzen and Pendleton. But, Wiley admits, his fashion ads are not what most people remember him for. Most people remember Dick and Jane.

Comments