Bennet Norrbo

- Melissa Delzio

- Apr 1, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Apr 6, 2020

Naughty & Nice

By Naomi Likayi

Written as a part of the Portland Design History Class at PSU

While admiring the mirrors and artwork on the walls of a Portland Pearl District art gallery bathroom, I saw one of Bennet Norrbo’s paintings hanging over the sink. I knew it had to be his work because of his painting style, his color use and the angular style of his line drawings. The reddish ochre hues against the light blue sky complemented each other with a white cat as the focal point. I walked from the gallery to the entrance of Katayama Framing and was introduced to Marilyn Murdoch. She was a close friend of Norrbo’s until his death, and I was here to conduct an interview with her about his life and artwork.

Bennet Norrbo was known as one of the greatest illustrators in Portland during the 1960s. He was a freelance illustrator at Studio 1030, a reputable design agency host to many talents shaping the Portland design scene. He later worked at Douglas Lynch and Associates, and his peers can vouch for his spectacular talent. Norrbo later transitioned out of the commercial art world, into fine art as a gallery artist. His medium varied from oils to acrylics in the two-dimensional sphere and had a chance to experiment with sculpting and film-making. As one of Portland’s social darlings, he was one of the highest-grossing gallery artists in town. He made a huge impression on those who were in his circle. The artist was known for having a unique temperament and would shift between being naughty and nice.

Early Years and Influences

He was born as Bennet R. Norrbo in Minneapolis, Minnesota on June 28, 1930. The family name “Norrbo” was uniquely created by his father and isn’t found elsewhere in his lineage. Bennet was born to Swedish immigrant parents and was the only child. The family moved to Portland, OR and he stayed there for the rest of his life. In conducting my research, Bennet had a passion for the fine arts as far back as high school. He attended Beaverton Union High School and would often enter competitions such as the Scholastic Arts Contest. As his talent progressed he won the Gold Key Medal Award and had his art displayed at the Meier & Frank store. He won a full-year scholarship to the Art Center Associate school in Kentucky. Later on, he went to a San Francisco art school before attending the Museum Art School back in Portland (currently known as PNCA). There he met future fellow Studio 1030 artists, Joe Erceg and Tom Lincoln who were also students. As a freelance illustrator at Studio 1030, Bennet had the chance to illustrate for big brands like Pendleton, Jantzen, Reed College and Georgia-Pacific.

Like most illustrators and artists, Bennet had figures who inspired his art style, as he was growing into his own. Nationally renowned artists such as Ben Shawn and David Stone Martin were among his influences. Martin was known for his illustrations on Jazz albums in the early 60s and Shahn founded the Social Realism movement. From colleague Tom Lincoln’s observation, their influence on Bennet’s work is demonstrated by their similar mark-making. The very sharp and angular and skirted lines are an indicator. Bennet also drew from his Swedish heritage, by studying illustrated Swedish fables and whimsical books.

Illustration Process

We currently live in an age where images are quickly compiled together sourced through stock photos and Pinterest boards at our disposal digitally. During the 60s as an illustrator, the process was more analog. I had a chance to write back and forth with Tom Lincoln, a Studio 1030 alum and exceptional graphic designer in his own right. I inquired about what he remembered and he shed light on Bennet’s process. “In those days Bennet, like most illustrators, kept a scrap file of every imaginable subject that struck their fancy as reference material: pages from magazines, mostly. There were no stock photo houses in those days, no Internet where one could google any particular subject, so the scrap images could occupy an entire file cabinet and saved a lot of time and leg work going to the local library for reference.” Sometimes coworkers at Studio 1030 would model for each other, or themselves. Bennet was also a model in one of his own illustrations, where he used his face as part of a Jantzen jacket advertisement.

From Commercial to Fine Art

Regardless of the fact that Bennet was succeeding as a commercial illustrator, he made a shift away from that type of work and devoted himself more fully to fine art. Despite leaving the commercial art industry, Bennet was still very successful in the fine art world. He was represented by Gallery West and had multiple juried and invitational exhibitions in various galleries, a few of them being Dorothy Cabot Best, Art Quake Invitational, White Bird and several others listed in his resumé. His paintings are a part of many public and private collections as well. His fine art often featured whimsical scenes of cats or women. The compositions were playful and full of movement. The colors were often warm hues, and he aligned oranges, blues and reds. One of Bennet’s favorite paintings shows a scene outside a movie theater. The red and orange hues dominate the painting, with a dark outline around the shape of the subjects as well as in them. This painting is important to Bennet because it shows him and his family going to a movie theater before moving to Portland. This documented a sweet moment in his family life that had the only painted image of his mom.

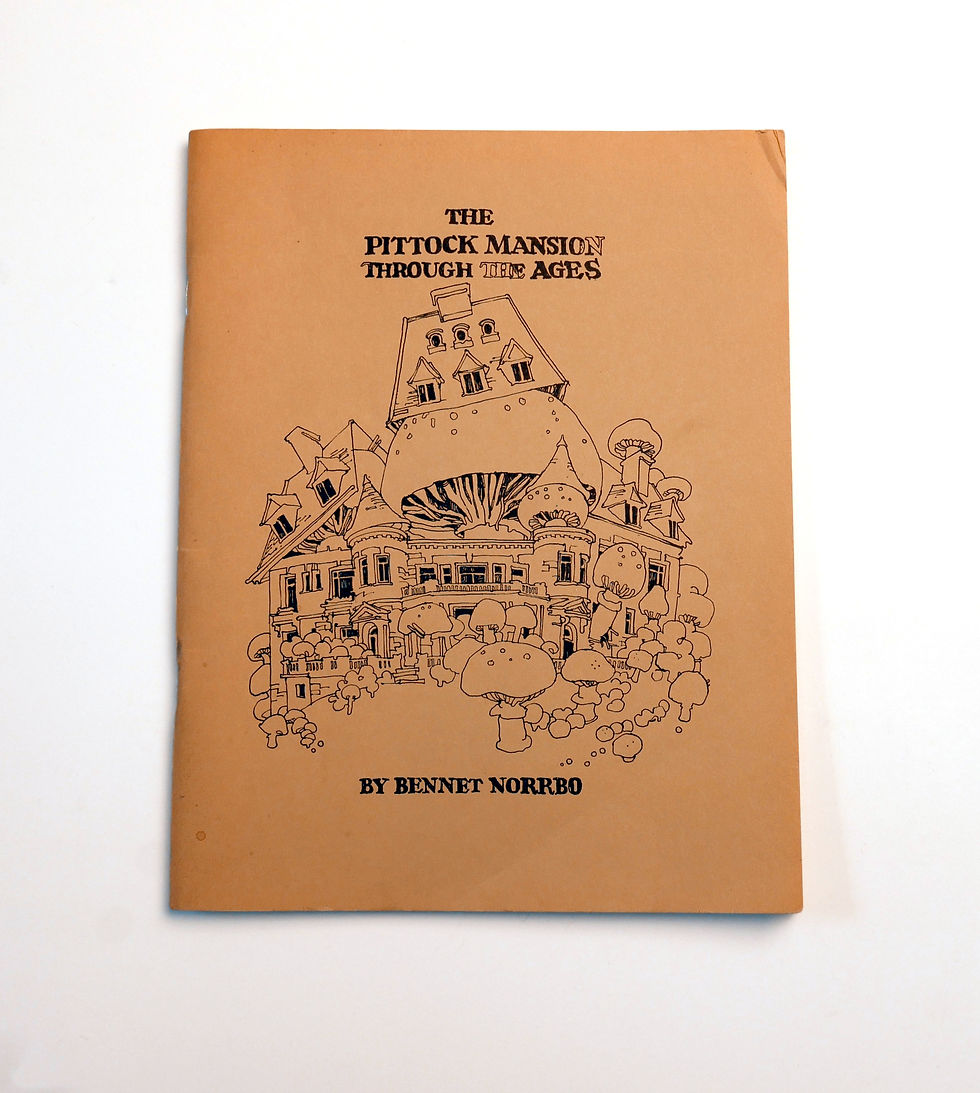

Bennet’s sense of humor and his liveliness were infused in many of his paintings and supplemental work. Despite being out of the commercial industry, Bennet published books and zines, one of them being, The Pittock Mansion Through the Ages. The zine is a fictional history of the Pittock Mansion on cream-colored pages and in his simple inked illustration style. Bennet purely injects his whimsy and quirkiness all throughout the book with the mansion shape-shifting and encountering odd guests. One story that struck me was the drawing of the mansion under US Army camouflage netting during World War I in order to hide from the Germans. At one point the camouflaged mansion had to be reexamined after “being considerably gnawed away by muskrats,” according to the caption.

Dual Personality

Marilyn met Bennet post-commercial art career and they became good friends. She had heard of the artist’s work, but says, “I had mistakenly thought he passed away. But, found out that he actually was alive. But the story got back to him, so he came to prove to me that he was alive and kicking. Then we just started seeing each other on a monthly basis.” From there came a friendship lasting 8-10 years. “I found him to be entertaining because he was so honest. You know honesty is a big thing with me and he was like a stand-up comedian he was very funny and I liked his humor, so it was fun to be with him.”

With Bennet’s impeccable talent as an artist, it’s often said that he had two sides to him or two personalities. Even though Bennet’s star sign is a Cancer, Marilyn strongly believed that his Gemini-Cancer cusp had an influence on his personality. There was a self-portrait of Bennet lying next to the cabinet of Marilyn’s archived work. The painting with a dark maroon background has Bennet wearing a light blue shirt holding a paint brush. “That picture divides between light and dark right down the middle. His daytime personality was very shy. [He] didn’t like to leave the house, didn’t want to talk to people,” Marilyn explained. His shyness is further emphasized in an archived story from the Beaverton Times on Bennet. One of the lines in the article says, “If, on one of the rare occasions when he attends an opening, Norrbo is cornered by an admirer asking what his paintings ‘mean’ he will mumble something and quickly escape.” It seemed as if flimsiness was a reoccurring theme in dealing with people in both his commercial and gallery art careers. But Marilyn rounded out her sentence explaining the painting, “That dark background is what he did at night … on the town. He was doing naughty things.” By that, she meant that he would frequent shady spots such as brothels and strip clubs as well as engage in heavy drinking. With such extremes of his personality, Bennet was said to be both shy and timid, but on the flip side was performative and humorous. From the outside eye, the juxtaposing sides between light and dark were hard to manage.

That darkness seemed to be responsible for him walking out of the commercial art industry. Colleagues noticed it too. Joe Erceg was a good friend of Bennet’s as well as a coworker at Studio 1030. In an archived interview, Joe explains Bennet’s temperament while working alongside him. “It made him nervous to work on commercial jobs. Eventually he quit doing it because his stress was too great, so he just continued his painting. He didn’t have a long and rich career as a commercial illustrator, because he just didn’t want to go through that. He worked on a few jobs for me, and he probably did illustrations for every designer in town before he just stopped.” Bennet maintained contact with Joe until his death as well as Charles Politz, another 1030 alum whom he was very fond of. Marilyn echoed the same sentiment during our interview on why the commercial industry wasn’t meant for him. “He couldn’t take the pressure of talking with clients, it drove him nuts, he really just had a hard time talking to people. And they worked as independents as far as I know— I think that’s what drove him out, his shyness not being able to face people and be serious.”

Another facet of his darker personality was his relationship with women. Since he was naughty, he liked painting naughty women. In his life, Bennet never married, had children or officially settled down. He had a flirtatiousness towards women in work and life, and could be very bold and exhibitionist depending on the setting. Marilyn shares one story as an example. It was the grand opening of p:ear, an artistic mentoring program devoted to homeless youth working and learning art on NW 6th and Flanders, and Bennet and Marilyn attended. The plan was to introduce the director of p:ear to Bennet as he would eventually help mentor the kids in the future. “So they invited me to this event. It was a black-tie event, everybody, really dressed up Bennet was a bit out of place and wore tweed jacket. So we sat down and he was already drunk. Well I should say high, but continued to drink. And it was such a display. There are women going by, and these are West Hills wealthy women, and he grabs one and put her on his lap and said, ‘I want a lap dance.’” I gasped and couldn’t help but laugh as Marilyn related the story. “I’m not kidding!” Marilyn assured. The farce did not fly well with Marilyn and she threatened to leave if he did it again. ‘“You do that one more time and I’m leaving you. He did that one more time.. and I left, ‘You find your own way home!’”

Believing in Endings

Bennet never was able to reconcile his two sides, and he created an alias for his darker work, Joe Hat. Bennet’s mother didn’t want him to disrespect the family name with his seedier artworks. The work was often suggestive and didn’t sell as well compared to pieces attached to his name. Those pieces would be sold at the Omni gallery. In one of his paintings, there’s a man in the center being tugged at by suggestive women who have charming expressions on their faces, while the man in the middle is in complete distress. Written on his suit are the words, “reveling with the prodigal son”.

Towards the later years of Bennet’s life, he felt frustrated with the fine art world. He felt that he had run his art into the ground and had become dispassioned. The complicated politics and trends in the art world felt commercial to him, which is interesting because he tried to get away from that in the commercial art industry. He felt the need to get away from Gallery West and didn’t want to do anymore shows. Bennet wrote in a note to himself, “It is absurd not to label gallery art for what it really is: commercial art. Callous and disciplined people can even make a living at it.” Bennet would often write notes on his observations of people and the settings around him, as well as what he dealt with internally. Sometimes he would write about himself as if he was another person. He would write about himself in a self-deprecating manner as well as depict himself as being picked apart by others. There’s a large self portrait of Bennet during an older stage of his life that is both dark and humorous and representative of his personality. Surrounding him are hands pointing at him, invading his personal space as well as one hand holding a machete and another squirting a water gun.

It was often said that Bennet was going to attempt suicide, but his friends never believed him. On the day that he passed, Marilyn remembered that it was a busy Saturday morning in 2013 when Bennet called. “I said, ‘Bennet I’ll call you back, I can’t talk right now.’ And he said, ‘I really need to talk.’ I said, ‘I’ll be with you as soon as I can.’” Marilyn called back after 5pm and there was no answer. By the time police found him, he was already gone. Bennet Norrbo was 83 years old. Five other people had the same story about Bennet’s attempted outreach and it left them devastated, but unsurprised. “I think he was very ill, and I think he got a bad report from his doctor ...probably his liver because he was a very heavy drinker.” Marilyn followed up. When I asked if an undisclosed illness might have prompted him to end his life, Marilyn thought it summed up his reasoning perfectly. “It seemed as if it didn’t make any difference to him because … he knew where the end was going to be.” Close friends knew that Bennet didn’t believe in beginning and endings. However, his suicide gave his life an abrupt end.

Despite this tragic ending, it’s good to remember that Bennet had an outlandish sense of humor that kept close friends around him entertained and was unabashedly himself. When we are young, we seem to care about what other people’s perceptions of us are, but Bennet didn’t seem to care at all. He was someone who was solely focused on the present. He would let all of his impulses run wild, and it was apparent in his work. He knew who he was and introspectively worked with such sensitivity. Bennet Norrbo was an exceptionally skilled fine artist and had a wild imagination that’s uniquely his own. Bennet’s remaining art pieces are currently sold at Murdoch Collections and all proceeds go to p:ear. What I learned from this research was that Bennet’s artwork embodied his character and the character of Portland. He loved Portland, and we love him too. •

Comments